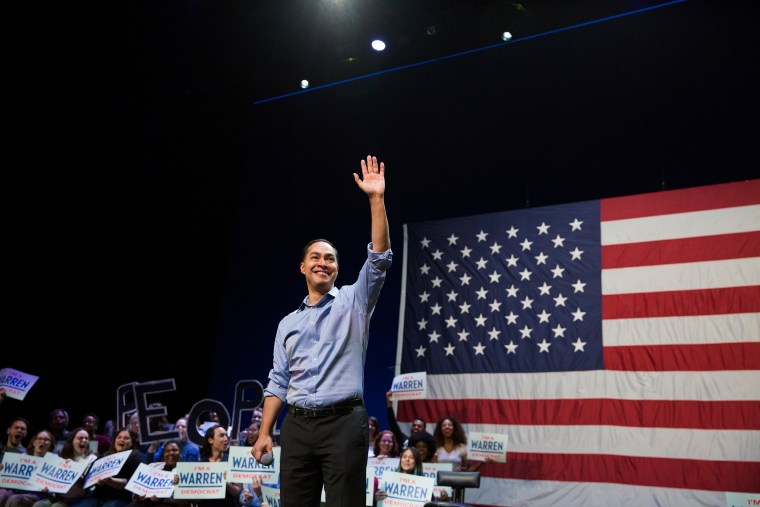

Julián Castro’s new philanthropic mission at Latino Community Foundation: helping Latinos help themselves

SAN ANTONIO — Julián Castro, who helped build Hispanics’ presence on the national political stage with his 2020 presidential bid, is now focused on building Latinos’ power to help themselves.

Just four months into his role as CEO of the California-based Latino Community Foundation, Castro has plunged the philanthropic-activist group into the high-stakes 2024 election with grants to Latino groups in Arizona, Nevada, other key battleground states and California, where a few congressional races could decide control of the House.

“The desire to go and do this work outside of California is a reflection of the urgency of lifting up the economic prospects of our community and making sure that people will exercise their right to vote,” Castro said in an interview at a Mexican restaurant in his hometown. Castro has remained in San Antonio but travels to and fro in the new position.

He has also signed up the foundation to take the lead in ensuring that Latinos, who are the overwhelming majority in California’s Imperial Valley, are not left out of any boom resulting from the lithium mining frenzy unfolding in region.

“In the Imperial Valley there is going to be a tremendous amount of wealth created, and we want to do our part to make sure it’s not just an extractive economy but that the people who live there benefit, as well, and not only economically, but in terms of the health, education, of greater opportunity in every way, quality of life,” he said.

The Latino Community Foundation is a nonprofit, nonpartisan philanthropic organization that invests in Latino-led organizations. It has worked largely in California and boasts having the largest network of Latino philanthropists in the country, investing more than $25 million in more than 375 grassroots, predominantly Latino-led organizations.

Its work ranges from investing directly in Latino groups to creating and administering what it calls “giving circles”: 17 groups of Latinos whose members each give $1,000 a year and then choose which community groups will receive the money they have collected. The giving circles have invested $2.9 million, it says on its website.

Castro said the foundation’s grants to Make the Road Nevada and the Arizona Center for Empowerment are a start to extending its work beyond California and to helping groups get more attention for Latino votes in those states. Both are progressive groups focused on registering and turning out Latino voters.

The foundation also commissioned BSP Research to poll 1,200 Latino registered voters — 400 in each state — to measure their takes on candidates and issues and their likelihood to vote.

“I want all candidates and all parties to pay attention to the needs of the Latino community,” said Castro, a Democrat who was mayor of San Antonio and housing secretary in the Obama administration. He also is a political analyst for NBC News and MSNBC.

Clear majorities of Latinos polled in each state said they planned to vote, but significant shares also said they were not well-informed about President Joe Biden’s or former President Donald Trump’s policy agendas.

“My point to political candidates is that it doesn’t matter what your ideology is, if you want to win, you need to address the concerns of the Latino community,” he said.

In an interview with NBC News in 2018, Castro said the subtitle of his memoir, “An Unlikely Journey: Waking From My American Dream,” released in the run-up to his presidential bid, refers to an understanding for many Latinos that it is not enough to just work hard for family and to achieve their own American Dream.

“Often, you also have to make your community and society better,” he said then.

That belief explains his enthusiasm for his new role overseeing a foundation that he said is assisting community groups so they can advocate for their neighborhoods, towns, cities and themselves before city councils and other government bodies about different issues or, for example, where to direct federal money that is awarded to their municipalities.

Castro cited examples of the foundation’s mission, such as its work with ALAS, a group that provides services to farmworkers and their families (the acronym is the Spanish word for “wings”; it stands for Ayudando Latinos a Soñar, or Helping Latinos Dream). The foundation also has worked with the Community Water Center, which focuses on ensuring safe and affordable water for communities in the San Joaquin Valley of California.

For more from NBC Latino, sign up for our weekly newsletter.

“There’s a lot more room for organizing Latino communities in any number of states across the country and investing in Latino- and Latina-led nonprofits across the country,” he said.

“Traveling throughout the country, I’ve found that you have — both in areas that have huge Latino communities and also in small pockets — this dearth of representation … on school boards, on city councils, on boards and commissions, and oftentimes you also have a lack of capacity of nonprofits to serve the Latino community. We ultimately want to be a part of building that capacity up,” he said.

Harnessing Latino philanthropy — both formal and informal

Castro has entered the philanthropic arena at a challenging time. According to Hispanics in Philanthropy, less than 1% of philanthropy funding supports causes benefiting Latino communities. Hispanics in Philanthropy, which calls itself the largest transnational network of givers, also is devoted to raising up Latinos economically and strengthening their leadership and influence.

A report it released last year found that Hispanic contributions to charities fell in 2018, the latest year for which information was available, as they did for all other groups. But the decline was greater for Hispanics, dropping from 44% of Latino households giving to charitable organizations to 26% in 2018.

Nonetheless, Castro expressed optimism for growing what he said is an already existent, formal and informal, unacknowledged Latino philanthropy.

Latinos, he said, are often incorrectly seen as less philanthropic than other communities. But Latinos give at church, in neighborhoods, to family members and in traditional ways. The Latino Community Foundation is trying to foster philanthropy at the grassroots level and among professionals who have reached their dreams and feel they want to give back to their communities, he said.

“We have been part of the story of American progress for a long time,” Castro said. “That means our community is fully invested in the future of our country and the destiny of America is intertwined with the destiny of the Latino community like never before.”