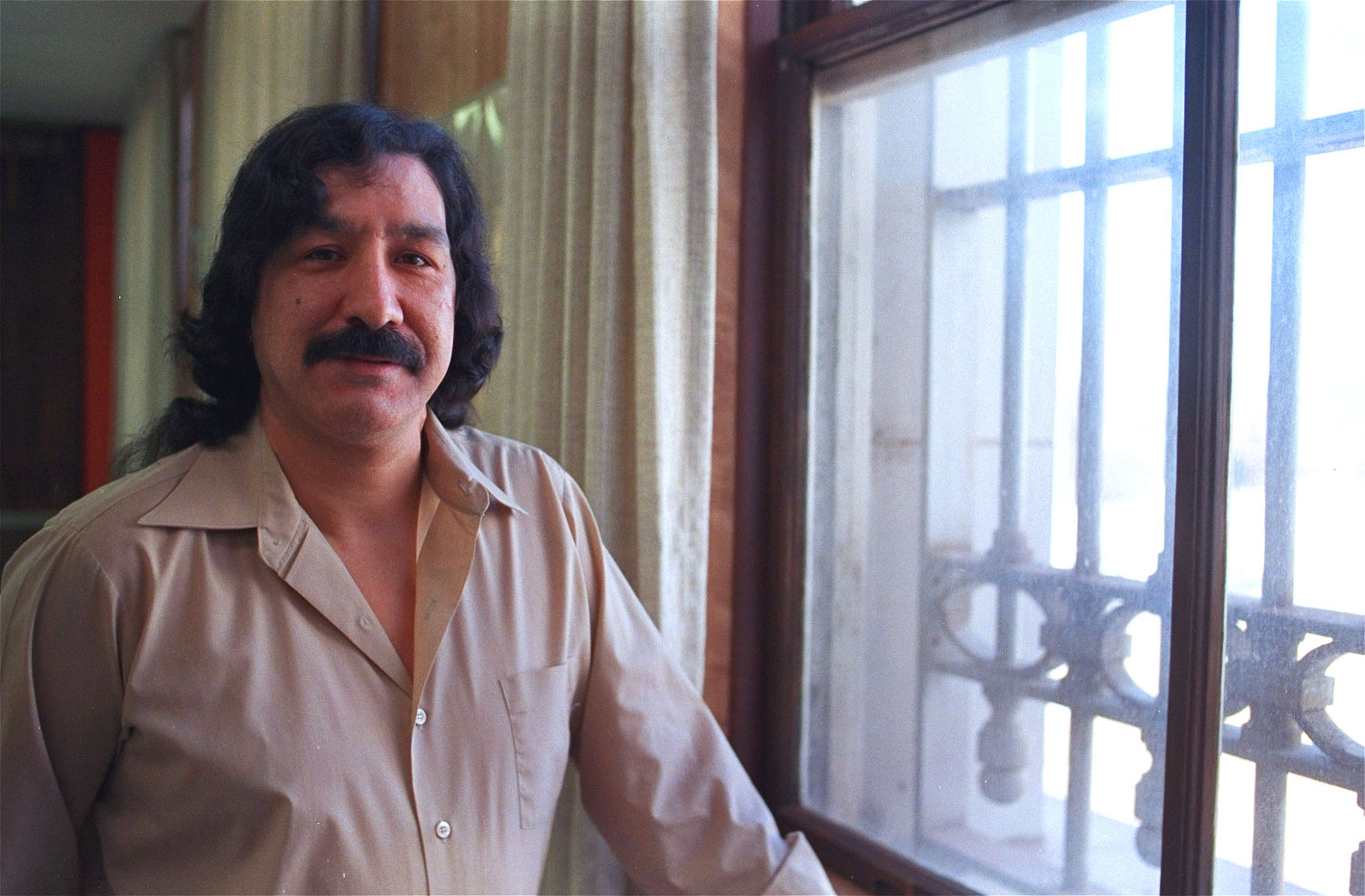

Leonard Peltier, Native activist imprisoned for nearly 50 years, faces what may be ‘last chance’ parole hearing

Native American activist and federal prisoner Leonard Peltier, who has maintained his innocence in the murders of two FBI agents almost half a century ago, is due for a full parole hearing Monday — his first in 15 years — as his supporters fear he may not get another opportunity to advocate for his release.

A lawyer for Peltier, 79, said he has been “in good spirits” as he prepares for the hearing at the Federal Correctional Complex Coleman in Florida.

“He wants to go home and he recognizes this is probably his last chance,” attorney Kevin Sharp said. “But he feels good about presenting the best case he can.”

Sharp said medical and re-entry experts would be called to support Peltier’s case for parole, and that hearing examiners and the U.S. Parole Commission will have letters from his community and prominent figures to review.

Over the decades, human rights and faith leaders, including Pope Francis and the Dalai Lama, and Nobel Peace Prize recipients such as Nelson Mandela and Bishop Desmond Tutu have backed Peltier’s release.

Apart from the decades of scrutiny surrounding how Peltier’s case was investigated and his trial was conducted, Sharp said, he believes his age, nonviolent record in prison and declining health, including diabetes, hypertension, partial blindness from a stroke and bouts of Covid, should be accounted for as the commission determines whether to grant parole.

The federal Bureau of Prisons “does not say he is a danger,” Sharp said. “This is about have they extracted enough retribution,” he added of the federal government’s resistance to Peltier’s previous bids for parole, given that the crime involved law enforcement agents.

At his 2009 parole hearing, an FBI official argued that time has not diminished “the brutality of the crimes,” and that while Peltier claimed his innocence, “he has resorted to lies and half-truths in order to sway public attention from the facts at hand.”

Paroling Peltier, who was sentenced to two consecutive life sentences, would have only promoted “disrespect for the law,” Justice Department officials said at the time.

FBI Director Christopher Wray said in a statement Friday that the agency “remains resolute” in its opposition to Peltier’s release, citing how his appeals have been denied and that he had even escaped from a California prison in 1979 but was captured three days later.

“We must never forget or put aside that Peltier intentionally murdered these two young men and has never expressed remorse for his ruthless actions,” Wray said.

The arrest

On June 26, 1975, FBI agents Jack Coler and Ron Williams were on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota to arrest a man on a federal warrant in connection with the theft of cowboy boots, according to the agency’s investigative files.

While there, the pair radioed that they had come under fire in a shootout that lasted 10 minutes, the FBI said. Both men were killed by bullets fired at close range. According to the officials, Peltier — a member of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians and then an activist with the American Indian Movement, a grassroots Indigenous rights group — was identified as the only person in possession of a weapon on the reservation that could fire the type of bullet that killed the agents.

But dozens of people had participated in the gunfight; at trial, two co-defendants were acquitted after they claimed self-defense. When Peltier was tried separately in 1977, no witnesses were presented who could identify him as the shooter, and unknown to his defense lawyers at the time, the federal government had withheld a ballistics report indicating the fatal bullets didn’t come from his weapon, according to court documents filed by Peltier on appeal.

But the FBI has maintained his conviction was “rightly and fairly obtained” and “has withstood numerous appeals to multiple courts, including the U.S. Supreme Court.”

Still, other officials have spoken out in support of him over the years. Retired federal prosecutor James Reynolds, who supervised Peltier’s post-trial sentencing and appeals, wrote to President Joe Biden in 2021 asking him to commute Peltier’s sentence because it would “serve the best interests of justice and the best interests of our country.”

“He has served more than 46 years on the basis of minimal evidence, a result that I strongly doubt would be upheld in any court today,” Reynolds wrote.

Peltier, in a phone interview from prison with NBC News in 2022, said he had hoped mounting pressure from Democratic members of Congress would convince Biden to grant him clemency, and possibly allow him a new trial to prove his innocence.

“I have a last few years,” Peltier said, “and I got to fight.”

Parole process

Peltier falls into a small category of mostly elderly federal prisoners who committed their offenses before November 1987 and can petition for parole from the Justice Department’s Parole Commission. Congress eliminated federal parole for inmates who committed offenses after that date because of new sentencing guidelines.

At a hearing, an examiner is in charge of reviewing the inmate’s case and hearing from witnesses. The hearing examiner’s recommendation on whether to grant parole moves to at least one other examiner who does not attend the hearing, and the ultimate decision then falls to a parole commissioner — who is nominated by the president, confirmed by the Senate and may be a former law enforcement official, educator or lawyer.

If the parole commissioner agrees with the examiners’ recommendation, that becomes the official decision. But if the first parole commissioner disagrees, a second commissioner must concur with either that commissioner or the examiners.

Such a layered process can appear detrimental to inmates if “the thread is lost,” said Charles Weisselberg, a Berkeley Law professor who has written about the “dysfunction” of the commission.

In addition, the Parole Commission typically has five members, but it has had only two since about 2018, Weisselberg said.

The Senate has not moved on filling the commission’s vacant seats. Weisselberg said having fewer commissioners to deliberate gives “greater power” to the hearing examiner, and “as a practical matter, it virtually eliminates the right to a meaningful parole appeal.”

Weisselberg has suggested the process can be streamlined with a magistrate judge as the arbiter. The Parole Commission did not return a request for comment.

Peltier’s supporters are hoping for parole but say Biden, who has not commented on the case, can still have him released on compassionate grounds.

“Mr. Peltier deserves the dignity to live the rest of his life outside the confines of a federal prison cell,” said Rep. Raúl Grijalva, D-Ariz., adding that “it is not too late to grant him the remaining years of a life that the federal government wrongfully stole from him so many years ago.”