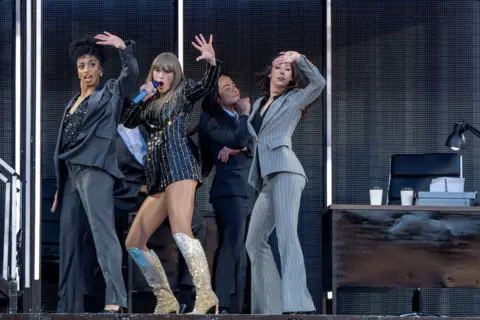

How ‘Swiftonomics’ is impacting the music industry

By Douglas Fraser, Business and economy editor, Scotland

PA

PATaylor Swift is not just a musical phenomenon, but a business unicorn too.

The Eras tour which has arrived in Edinburgh is reckoned to be pushing her wealth well north of $1bn (£785.51m).

Forbes, the money magazine, reckons she is worth $600m (£471m) from performance and her back catalogue is worth as much, while she has around $125m (£98.2m) worth of real estate.

Other musicians who have reached such heights have done so by investing their musical earnings in other ventures.

This daughter of Pennsylvania, and of a financial broker, mints money with astute leverage of her market power. It’s known as Swiftonomics.

She is reputed to demand more than 100% of gross ticket sales, leaving the promoters to make their margins from sales of food and drink and extras. That’s why they want ticket-holders to get there early.

By doing multiple nights at one venue, she cuts touring costs and forces her fans to come to her.

As Edinburgh is showing and London soon will, they do so in very big numbers, some over long distances.

We are told that financial savvy is part of her appeal to the fanbase.

She took on Apple over royalties for tracks streamed on its music service, and she won. She did the same with Spotify, refusing to let her songs go on its free-to-use service.

PA

PAHarvard Law School uses her as an example of negotiating power, saying in its teaching materials: “Taylor Swift was able to turn her back on negotiations with Spotify because she had no shortage of other negotiating partners eager to work with her.”

The 34-year old is smart and has become very rich both by dictating terms to music industry bosses and by selling to that fan base. And they love her for it.

After she sold the rights to her earlier recordings to an investment company, she rebelled against its constraints on her artistic freedom.

While the investor had rights to those recordings, she retained the composer’s rights, and has re-recorded multiple albums, persuading her fans to buy the re-records as the preferable and definitive collector’s item. Fans do so over the originals by a ratio of 4:1.

This is not just about streaming.

The return of vinyl records has put them back into the basket of commonly-purchased goods included in the inflation survey for the Office for National Statistics.

PA Media

PA MediaTaylor Swift has a sizeable share of that vinyl market, often selling to people with no turntable, but who choose to collect for the artwork.

Is she a one-off? Possibly. But Scots author Will Page, a former chief economist at Spotify, reckons she has skilfully captured the opportunities arising out of fundamental disruption.

Others may not reach her heights of financial success, but he thinks she points the way for others to follow.

Mr Page said: “She has raised the bar in terms of what an artist can achieve in this complex value chain, both from streams and tickets.”

So let’s take a look at some of the trends in the music industry that Taylor Swift represents.

Digital streaming threatened to destroy the industry while downloads could be pirated.

But the industry fought back and streaming replaced sales of vinyl, cassettes and, more recently, CDs and DVDs.

That put immense market power in the hands of a small number of platforms.

Spotify is focused on music and podcasts, while that is only part of the business model for Amazon, Apple and YouTube.

PA Media

PA MediaBut distribution costs of streaming are tiny compared with the price of boxing up hardware and trucking it out to shops.

Without them, artists can claim a much higher proportion of a download sale than they could earn from a CD – as much as 30% compared with a maximum of 15%.

Streaming also offers unlimited space for people to enter the market place.

Mr Page said the “supply side explosion is beyond anyone’s imaginings”.

He added: “Spotify can have 120,000 tracks uploaded in one day, which is more than all the music released in 1989.”

Mr Page said the industry was making more money but had “more mouths to feed,” with nine million creators on Spotify alone.

In 2009, the Performing Rights Society had 50,000 song-writers. It has 173,000 now.

He said: “The population of artists and songwriters in the UK has tripled since Spotify’s launch. That’s a positive story. How do you feed them all? That’s another story.”

Trends from downloading

Digital downloads let artists like Taylor Swift launch her album as a global event. Everyone can download on that day.

Two trends arise from this. One is that it’s easy to reach your fan base, and listeners to new music are increasingly turning to those who sing in their own language.

The top 10 most streamed tracks in each European country can be dominated by those countries’ musicians.

So the dominance of English language is waning. That makes it more difficult to market international stars.

The other is that listeners to music and viewers of song videos turn to streaming platforms to sample new bands.

They are less likely to go out to pubs and clubs, in the hope of seeing the Next Big Thing while it’s still small.

The pipeline of bands learning their trade in smaller venues is slowing, which alarms some of those in bigger venues, particularly when they look at the age profile of the performers who are able to fill them.

That takes us to the split in earnings between performance and recording.

It used to be that bands went on the road to promote their latest album. Now they produce an album to promote their tour.

PA Media

PA MediaSince the pandemic, touring has become an even bigger part of the music industry’s revenue base.

Having been cooped up for months and unable to see live performance, music fans grabbed the opportunity to get back to what they were missing.

Will Page has looked at the UK numbers for 2022, and they are startling.

Recorded music earned more than £2bn, much of that through streaming services and some from the re-discovery of vinyl.

In live music, there were fewer gigs, down 26% on the pre-pandemic year of 2019.

Stadiums and festivals were down 14%, arenas were down 22% and theatre venues down 43%.

But people were willing to pay a lot more for tickets – £100 to £150 is not unusual – and revenue went up 22%, the total also rising above £2bn.

So across recording and performance, revenue rose from £3.2bn in 2019 to £4.1bn in 2022.

That’s a big bounce back from the pandemic, but one that is being focused more and more on big artists in big venues.

Back in 2012, the spend on live music was £1.3bn, and stadium concerts and festivals took in 23% of that.

Ten years later, the stadium and festival share of £2.1bn in takings had more than doubled to 49%.

Mr Page said: “It’s a much bigger share of a way bigger pie.”

Back catalogue investment

Returning to that decline in the pipeline of new performers coming through small venues, one question for the music industry is whether the sharply increased post-pandemic pricing for big venue gigs is absorbing the money available.

And whether it is leaving music-attenders little left over to buy cheaper tickets in smaller venues.

Mr Page is soon to update these figures for 2023, and that will show if there has been an impact from consumer price inflation and squeezed household budgets.

There could have been a bounce-back from the pandemic which is not sustained after the first year without facemasks.

The other major trend in the music industry is towards big finance moving in to buy up assets.

Taylor Swift embraced that opportunity, but discovered the downside for an artist who continues to produce and who wants control over the way her recordings and songs are used.

However, for older performers, and dead ones, there’s a big market in buying back-catalogues.

The Music Business Worldwide (MBW) website tracks the industry, and reported that the investment in back catalogues in 2020 by one of the biggest players, Universal Music Group, was more than $1bn, a large part of that for Bob Dylan’s songs and recordings.

It fell the next year to $459m (£360m).

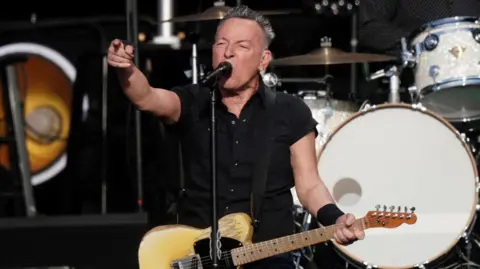

PA Media

PA MediaThe numbers are rarely made public, but there are industry estimates of Sony paying $550m (£432m) for Bruce Springsteen’s publishing and recorded music.

Paul Simon’s publishing rights changed hands for a reported $200m (£157m).

And David Bowie’s song catalogue was sold for an estimated $250m (£196m).

The appeal is through tax as sale of an asset is taxed at a lower rate than earnings from that asset.

The appeal is also that a large company takes over responsibility for sweating that asset financially.

It can look forward to lots of earnings to come.

Pop and rock music may seem ephemeral or disposable, but people keep going back to tracks they liked before rather than focusing on the latest thing.

The data from streaming shows that it is ‘catalogue’ classified as older than 18 months, that has as much as 80% of the market.

After several busy years of recording music and touring, Taylor Swift can afford to kick back and relax with her pile of earnings.

But she seems financially as well as creatively driven, and unlikely to hand over those rights any time soon.