Legion’s founder aims to close the gap between what employers and workers need

While taking a long road trip across the U.S. years ago, Sanish Mondkar realized that there were stark, problematic disconnects between employers and the staff they employ.

To critics of late-stage capitalism, that might sound like an obvious observation. But Mondkar, who has a master’s in computer science from Cornell, says that seeing the issues up close made all the difference.

“Traveling from town to town, I couldn’t help but notice the perpetual ‘for hire’ signs plastering the windows of countless labor-intensive businesses such as retailers and restaurants,” he said. “Simultaneously, I saw employees frequently changing jobs, yet struggling to make a living wage. This disparity between employers’ needs and workers’ realities struck a chord with me.”

Inspired by this experience, as well as stints at Ariba as EVP and chief product officer at SAP, Mondkar set out to build a startup that helps companies manage their workforces — particularly contract and gig workforces. His venture, Legion, today announced it raised $50 million in funding led by Riverwood Capital with participation from Norwest, Stripes, Webb Investment Network and XYZ.

“My objective was to rebuild the enterprise category of workforce management in order to maximize labor efficiency for the businesses and deliver value to the workers simultaneously,” Mondkar said. “I wanted to differentiate the company itself with a focus on intelligent automation of WFM and the employee value proposition.”

Legion is designed to support customers — employers like Cinemark, Dollar General, Five Below and Panda Express — in managing their hourly staff by automating certain decisions, like how much labor to deploy where and when to schedule workers. Taking into account demand forecasting, labor optimization and the preferences of employees, Legion’s platform generates work schedules.

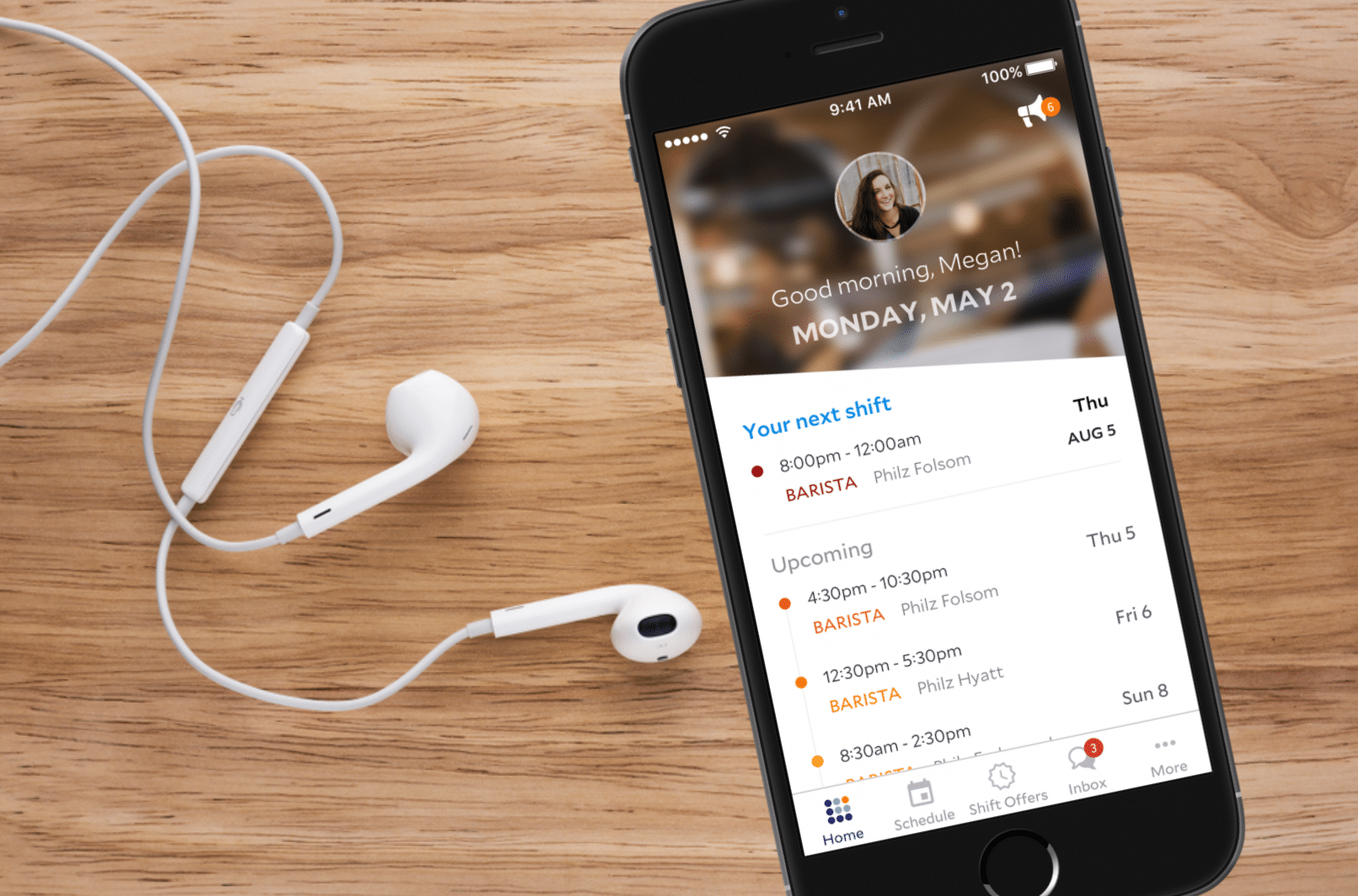

Employees whose companies are on Legion can use its mobile app to request how they want to work and set their preferred hours. Legion’s algorithm then tries to match the preferences of workers with the needs of the business.

Legion also incorporates performance management tools and a rewards program of sorts.

“We use algorithms trained on a blend of customer data and third-party data, which Legion aggregates from its partners,” Mondkar said. “This integration allows for forecasts for planning and resource allocation.”

In addition to the base scheduling features, Legion — very on trend — is leaning into generative AI with a tool called Copilot (not to be confused with Microsoft Copilot). Copilot answers questions about work informed by an organization’s employee handbook, labor standards and training content. In the coming months, Copilot will gain the ability to summarize work schedules and fulfill requests to add or delete shifts or change staffer assignments.

“In order to attract and retain staff, companies employing hourly labor must emulate gig-like flexibility,” Mondkar said. “Legion provides this with the intelligent automation of scheduling. Managers can match staff to projected demand, closing the gap between the needs of employees and the needs of the business.”

That’s all well and fine, but two concerning things stand out to me about Legion: its privacy policy and earned wage access (EWA) program.

Legion says it stores customer data for seven years by default — a long time by any measure. More concerningly, the data includes personally identifiable information like workers’ first and last names, email and home addresses, ages, photos and work preferences. Big yikes.

Legion says the data is necessary to “facilitate scheduling in compliance with labor regulations,” and that users can request that their data be deleted at any time. But I question the ease of the deletion process — and just how transparent Legion is about its data retention policies to customers.

My other gripe with Legion is InstantPay, Legion’s EWA program, which lets employees access a portion of their earned wages ahead of their scheduled paydays. Legion charges workers $2.99 for instant earned wage transfers, while next-day transfers are free — that might not sound like very much, but it can add up for a low-income worker. Legion pitches this as a benefit for hourly workers that gives them “greater flexibility” and “control” over their finances, as well as a business retention tool. But EWA programs are under scrutiny from policymakers, consumer rights advocates and employers. Legion’s mobile app.

Some consumer groups argue that EWA programs should be classified as loans under the U.S. Truth in Lending Act, which provides protections such as requiring lenders to give advance notice before increasing certain charges. These groups say EWA programs can force users into overdraft while effectively levying interest through fees.

In addition, it’s not clear whether EWA programs are a net win for employers. Walmart recently tried to combat attrition by giving hourly staff access to wages early. Instead, it found that employees using EWA tended to quit faster.