Retirement anxiety brings battleground blues for Biden in states like Pennsylvania

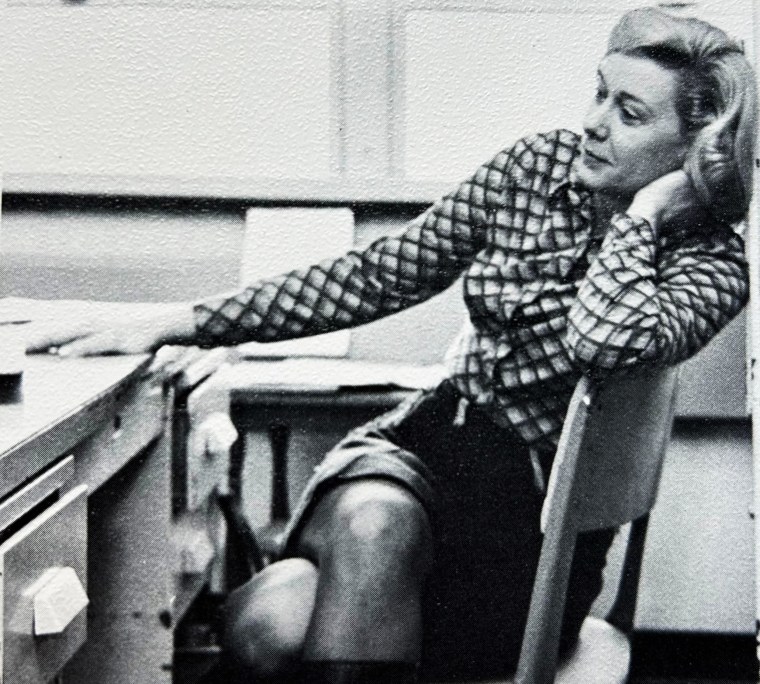

For 30 years, Jacqualyn James taught American history and psychology to high school students in East Stroudsburg, Pennsylvania, in the eastern part of the Keystone State.

A graduate of Bucknell University, she became a teacher to support her family after she and her husband divorced. “I considered it a very important thing for young people to learn about the history of this country,” she told NBC News, estimating that she’d taught 7,000 students by the time she retired in 1998.

During her teaching years, James paid regularly into her pension, the Public School Employees’ Retirement System of Pennsylvania. “I expected it to last my lifetime,” the 88-year-old said.

While her $25,000 yearly pension has indeed lasted, because of a fluke in Pennsylvania law, it is now worth half of what it was when she retired. That’s because James and roughly 70,000 other retired public employees in the state have not received a cost-of-living adjustment on their monthly payments for more than 20 years. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, every dollar in pension payments James was promised when she retired is worth 51 cents today.

James and her unlucky former colleagues retired before the enactment of a 2001 state law known as Act 9 that increased pension benefits for public workers. Some of those 70,000 people, whose average age exceeds 80, are experiencing significant financial hardships. Many have no access to Social Security, as is the case with roughly 40% of all public school teachers across the nation, according to the National Association of State Retirement Administrators.

Overall, the U.S. economy is humming, the data shows, a situation that typically favors a sitting president in an election year. But financial anxiety among voters in battleground states is complicating the 2024 picture. In Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Nevada, North Carolina, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin, the so-called misery index, an economic measure combining four years of inflation with the current level of unemployment, is running higher than in states that dependably vote Democrat or Republican, a recent analysis by Bloomberg News shows.

Retired public employees like James are not the only ones facing rocky retirements in Pennsylvania. As many as 2 million private sector employees in the state, or 1 in 3 workers, have no access to retirement plans at their workplaces, according to John Scott, project director for retirement at the Pew Charitable Trusts, a nonprofit organization that researches public policy issues. Indeed, unless Pennsylvanians save more, Pew researchers predict, state taxpayers will need to provide an estimated $14.3 billion in the coming decade to support older households with inadequate retirement savings.

“If you look at the data, how little people have saved for retirement is really a function of having access to a retirement plan,” Scott told NBC News. “Two million workers not having access speaks a lot to why there is a sense of insecurity about their futures.”

Even those who have been putting aside money for retirement are uneasy about their futures. Victor Martens, 55, owns a small construction company in Mount Pocono, Pennsylvania, with his son and has contributed regularly to his individual retirement account. “You save enough for retirement but then you have inflation,” he said. “And prices just keep going up.”

An afterthought

For decades, pensions like the one James relies on, or those like it that were offered by corporations, were the most common retirement vehicle for workers. Today, self-directed savings plans such as 401(k) plans and individual retirement accounts, or IRAs, are the norm.

Amid this shift, many Americans do not have any retirement savings at all. Last fall, the Federal Reserve Board published an analysis of U.S. families’ finances and found that just more than half — 54.3% — had a retirement account in 2022, up from around 50% in 2019. The median amount in those retirement accounts is $86,900, the analysis said. For those closer to retirement age, ages 55 to 64, the median amount held in a retirement account in 2022 was $185,000 nationwide.

Having a retirement account does not necessarily mean a saver has enough money to retire comfortably. An estimated two-fifths of American workers have inadequate savings set aside to maintain the standard of living they enjoyed while working, according to the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College. Although this figure has improved since 2019, it concerns policymakers.

In Pennsylvania, the share of households with people 65 and older and annual incomes of less than $75,000 — an indicator of financial vulnerability — is expected to increase by 17% from 2020 to 2035, according to research from Pew Trusts.

The problem for many workers in Pennsylvania and elsewhere is that their employers do not offer 401(k) plans and without an automatic deduction from a paycheck, saving for retirement is an afterthought. Small businesses, in particular, find it expensive and complicated to set up retirement plans for their workers, Scott of Pew Trusts said. “You can save for retirement out of the workplace, but very few do — just 13% of Americans,” he said. “There are a lot of steps you have to go through.”

Fifteen states have devised a solution to this problem — passing legislation to mandate government-run automated savings plans that make it easy for workers to set aside money for retirement. Oregon was the first to create an automated savings plan in 2017 and seven other states now operate such accounts, with another seven coming on stream soon. The progress has been promising, Scott said — in the six states whose plans have operated the longest, 850,000 workers have set aside $1.3 billion for their retirements.

A bill to create such a savings plan for Pennsylvania workers was proposed in 2023. Under the program, known as Keystone Saves, workers would voluntarily forward payroll deductions into a fund overseen by the state and operated by a third-party financial firm. The bill has not yet passed both legislative houses.

Walt Rowen, a third-generation owner of the Susquehanna Glass Company in Columbia, Pennsylvania, is enthusiastic about Keystone Saves. He employs 40 people making decorative bar and kitchenware in his factory, about an hour west of Philadelphia.

“When I first heard about it, I thought this thing would be absolutely perfect,” he said of Keystone Saves. “Quite a few people have worked for us for 25 to 35 years. We know the impact — when they finally retire and if they haven’t put enough money aside, it’s tough.”

Rowen said he considered creating a 401(k) plan for his workers about 15 years ago but found it would cost between $2,000 and $4,000 per employee to set up and operate. Besides, he said, a lot of his workers told him they wouldn’t participate.

Now, he says, offering such plans could help attract workers. “Over the years, I’ve had people say, ‘I’d love to come work for you, but I have a 401(k) plan at my job now,’” Rowen said. Keystone Saves would solve that problem, he said.

$1.4B to Wall Street

Pending legislation would also solve the problem of the 70,000 retired workers like James who have missed cost-of-living increases in their incomes over the decades.

State Sen. Katie Muth, a Democrat representing the 44th District near Philadelphia, is one of several lawmakers sponsoring bills to give the retired state pensioners money she says the state owes them. “This is a pool of people that served the public in varying capacities,” Muth told NBC News. “This is a human rights issue.”

Muth and the other lawmakers backing COLA legislation estimate the costs at between $89 million and $125 million. A lot of money, to be sure, but Muth noted that Pennsylvania’s Rainy Day Fund, the state’s reserves for a financial downturn, contained $6.1 billion as of last fall.

Moreover, Muth said, the retirees’ privation is especially stark when compared with the fees that wealthy investment firms have generated advising the pensions over the years. “You can’t say the system is working when retirees are not having these cost-of-living increases, but their pension dollars are being invested with $1.4 billion in investment fees to Wall Street managers,” she said.

James has written letters and emails to lawmakers about the problem, to no avail. Adding to her ire: Pennsylvania lawmakers receive automatic cost-of-living adjustments in their pay.

One of those lawmakers is state Sen. Cris Dush, a Republican who chairs the government committee and who has declined to forward the COLA bill to the Senate floor for a vote. Dush did not respond to a request for comment.

As the effort to help the retirees languishes, their numbers are dwindling. During the most recent year, 3,444 beneficiaries died, Muth’s office said.

Michael Hurd is director and senior principal researcher at the RAND Center for the Study of Aging. The Pennsylvania situation, he said in an interview, is an example of a broken promise by the state to provide workers with a pension that rises along with the inflation rate.

“The average age of these people is 83, so they’re obviously not going back into the labor force to supplement their incomes,” Hurd said in an interview. “Individuals are not well positioned to handle these kinds of risks. It’s unconscionable. This should not happen.”

Meanwhile, James’ everyday costs keep rising. “Yesterday, I got my monthly trash collection bill and it went up $18,” she said in a recent interview. “A lot of the things I used to love doing, I don’t think about doing them anymore.”

Mostly, she says, she sits at her kitchen table watching the birds at her bird feeder.